Introduction

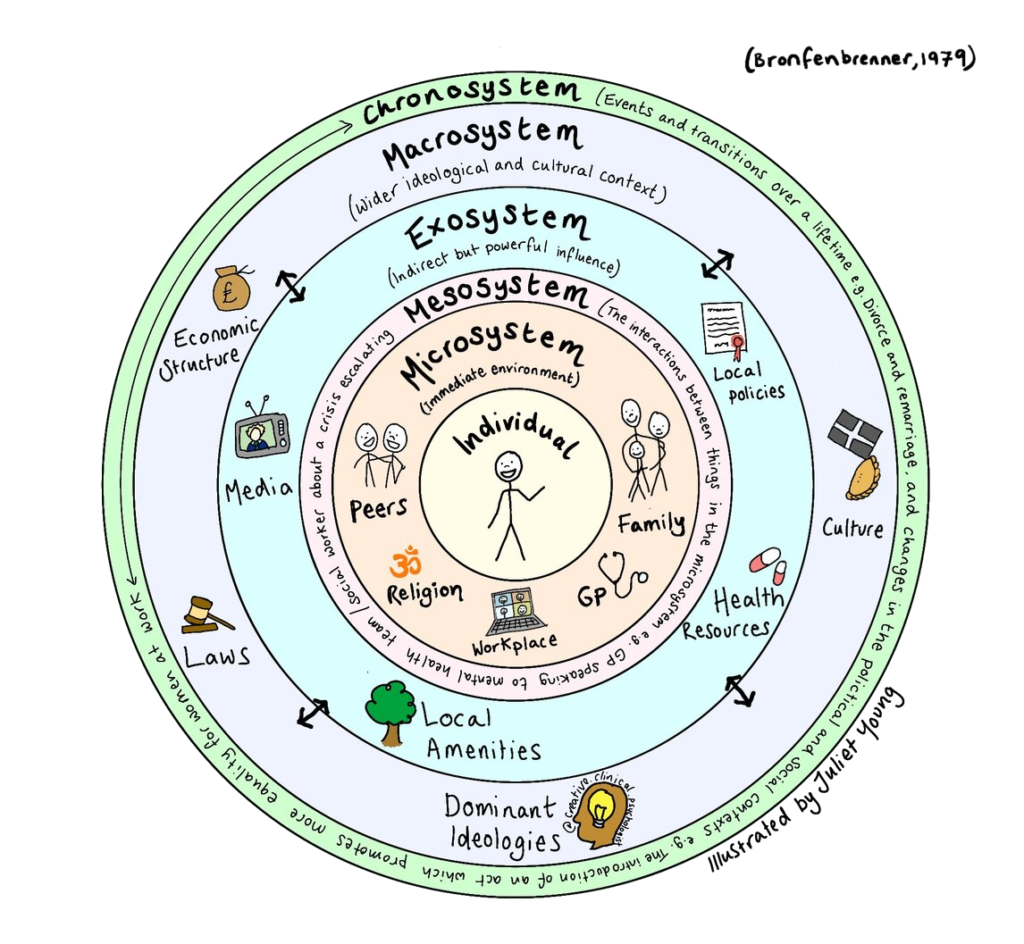

Although the public education system in the US equips students to succeed in their lives post-graduation, within each school lies a complex web of overlapping issues that prevents some students from achieving this success. There are also problems residing outside the school’s physical environment, specifically the struggle to bring students with high rates of absenteeism back to the classroom. There is a robust body of literature that exists within the realm of absenteeism which discuss the factors that may be contributing to absenteeism and/or various intervention strategies aimed to combat absenteeism. As absenteeism has many root causes, it therefore cannot be addressed using one approach. Each of the following three areas – school culture, mental health, and solutions – may be placed into one of the five categories of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Despite the nature of absenteeism being a crisis that extends beyond school grounds into the student’s life outside the classroom, it is a school-related issue, especially in Hartford, Connecticut.

Situated in the heart of the historical state of Connecticut is the State’s Capital, Hartford, where school absenteeism plagues the city’s public school system; this issue is especially prevalent in the city’s three comprehensive public high schools: Hartford High School, Bulkeley High School, and Weaver High School. According to the Connecticut Department of Education, “chronic absenteeism” is defined as a student missing 10%, or a minimum of 18 days, out of a 180-day academic calendar (CSDE, 2023).

Over the last decade, absenteeism rates in Hartford were on the decline, but this progress was disrupted in early 2020. March 2020 was the infamous month during which all Americans confronted the realities of the COVID pandemic, especially schools, where faculty, students, and their families were forced to transition to online and remote learning. Since then, although all three Hartford high schools have returned to in-person learning, not all students have returned to their classrooms and high school absenteeism in Hartford is on the rise.

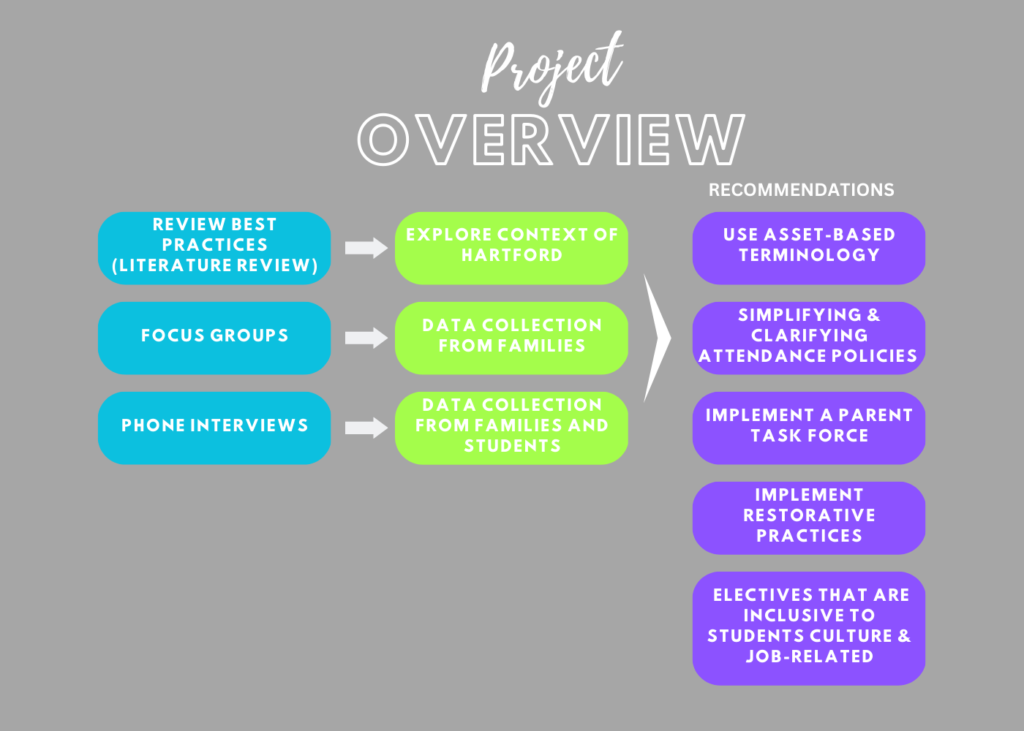

In an effort to discover the best possible ways to tackle this pervasive problem, Hartford Public Schools (HPS) seeks the input from those who are directly impacted by absenteeism: the families of students with high rates of absenteeism and the students themselves. In order to gain these crucial perspectives, HPS has reached out the Liberal Arts Action Lab to speak with HPS families and students in order to answer the following research questions: What are the root causes of absenteeism?, What are some possible solutions for absenteeism? and, How effective are the current protocols in bringing students with high absenteeism rates back to the classroom? Seeking answers to these research questions through considering the student as a being that exists within a bioecological system will lead to the development of strategies and resources to best address absenteeism.

Background

Research is being conducted through focus groups on three specific high schools within the Hartford Public Schools district. Focus groups are defined as a type of group interview consisting of combined local perspectives from people with similar characteristics. This includes Hartford Public High School, Bulkeley High School, and Weaver High School. In terms of data, Hartford Public High School has 789 enrolled students, 317 multilingual learners, 183 students with disabilities, and 633 students that qualify for free and reduced meals. Bulkeley High School has 592 enrolled students, 91% of which are qualified for free and reduced lunch and have a 55-58% graduation rate (“Bulkeley High School (2023 Ranking) – Hartford, CT”). Lastly, Weaver High School has an enrollment of 554 students, is in the bottom 50% for test rankings, and has 89% of the population eligible for free lunch (“Weaver High School (2023 Ranking) – Hartford, CT”). This data is all important when considering the factors that impact high school absenteeism in Hartford Public Schools.

The history of issues revolving around educational issues in HPS is deep and dates back decades. The Sheff v. O’Neill case was sparked in 1989 in order to prove schools in the Hartford region were segregated. The plaintiff Milo Sheff wanted the ability to choose where he and many others could attend schools. The result of the case was a voluntary desegregation plan which brought about the Open Choice program and magnet schools based on a lottery system (Connecticut Public Television, 2023). In order to bring in funding, priority is placed on attracting white students from the suburbs through the rehabilitation of the public schools, as opposed to building new magnet schools (Connecticut Public Television, 2023). Ultimately, the goal is to improve education and implement integration for all students.

Theoretical Framework

Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model

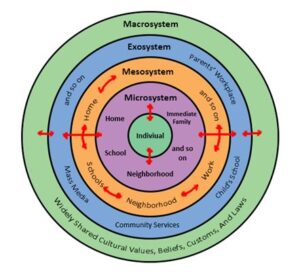

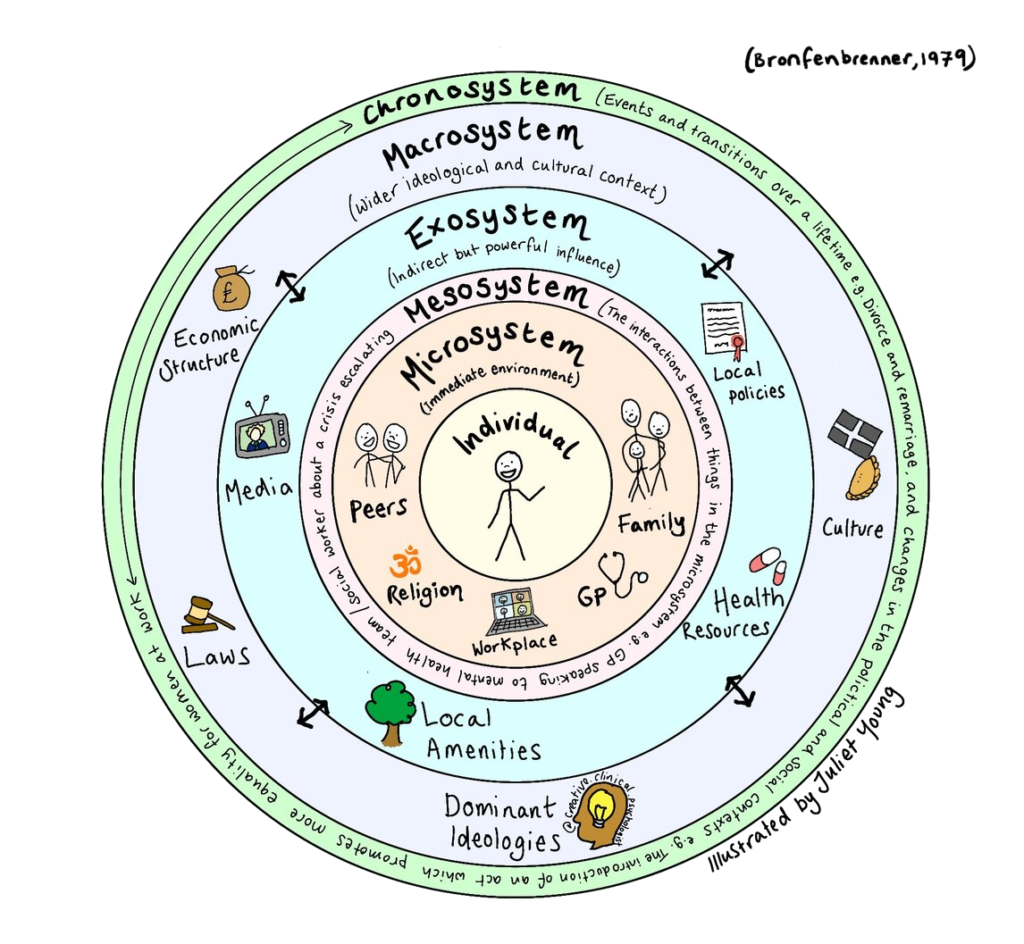

The causes of high absenteeism rates stem from many different areas of a student’s life and environment. We utilized Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1977) as a guide for categorizing factors related to absenteeims. Although the bioecological model is originally about human development, it provides a framework that is helpful in disucssing absenteeism. The model separates student influences beyond the individual into four distinct categories. The microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem and macrosystem(Singer, 2021). Microsystem refers to the closest influences on students such as parents, religion, friends, and school. Mesosystem is defined as the connection between the microsystems. This includes teacher-parent relationships and sibling-parent relationships. Exosystem is defined as environmental situations that students are not directly a part of, but it directly affects them. This includes their parent’s workplace, local policy changes, mass media, school districts and social services. Macrosystems are referred to as the cultural and societal components that impact students’ development and how students are raised. This includes social norms, economic systems, political systems, and nationality.

We used this model to guide our research because the bioecological model is not solely helpful in determining the causes of absenteeism, but also in finding solutions. The model’s categories help separate big-picture solutions from small-picture solutions. Smaller and typically more immediately impactful solutions address problems in the microsystem and mesosystem. Large policy changes and funding adjustments address problems in the exosystem and macrosystem and are more necessary for long term change. The model provides helpful framing for determining causes and solutions to high school absenteeism.

Findings

Exosystem

For the student practicing habitual absenteeism, schools often fail to provide students with the necessary support and motivation that will encourage them to consistently attend. Therefore, an unwelcoming school culture is a significant reason as to why students do not attend school. School climate is defined as the quality of the school’s social and educational environment. This includes the schools culture regarding academic support programs, mental health support services, school safety and teacher-student relationships. As social creatures, there are many benefits to interacting with other people – especially at a young age. Finding friends, teachers, and classmates for support fulfills a student’s need for belonging, companionship, identity, and comfort (Hartnett, 2007, p.43). As a student develops and spends more time interacting with people outside their immediate family, they generally fall into the influence of their peers, classmates and communities. Studies have asserted that peers have more influence over each other than their parents do (Hartnett, 2007, p.43). However, as students begin to adopt identities and find their belonging in communities, it becomes apparent that school culture is not accepting of all groups. A deep-dive into several high schools across Washington state revealed, for example, that schools endorse certain social groups like “jocks, academics, student leaders, cheerleaders, and band members” while groups like “Geeks, Goths, Tomboys, Stoners, Lesbians, and Gays” are often ostracized and treated unfavorably by the school culture. (Hartnett, 2007, p.37). his study showed the potential for school culture to inadvertently promote some groups and marginalize others; consequently, the social groups that are not promoted, acknowledged, or accepted by their teachers and peers find that not attending school is the best option in order to finding a safe space for themselves.

Specifically, studies have shown that those who identify as a sexual minority youth (SMY) are more prone to absenteeism because they are less likely to have been accepted within mainstream school culture. It has been documented that, “sexual minority students report greater victimization or bullying in school than heterosexual students” (Burton et al. 2013, p. 38). For SMY who do not adhere to the mainstream school culture, they “reported higher rates of being assaulted in school by a peer with a weapon and higher rates of skipping school due to fear” (Burton et al. 2013, p.37). Naturally, being in a school culture that is unwelcoming and abusive towards certain groups leads to absenteeism and lower grades. In a recent article from 2020, it is stated that, “studies show that social identification at school foretells several outcomes, including positive attitudes regarding school, increased determination to learn…and more engagement in academic environments” (Nerveza-Clark, 2020, p.20-21). Thus, the relationship between identity and academic involvement is closely linked. Going forward, it should be acknowledged that all these studies point to the need for change in school culture to increase a sense of belonging among all students”. his can be done through the implementation of “difficult conversations” inside classrooms so that educators and classmates can understand the perspectives of one another with the goal of creating a welcoming classroom climate. This is important because “establishing an environment for self-questioning and self-reflective skills expands students’ conscious understanding of themselves within their social environment and enables them to become powerful change agents in their communities (Werman et al. 2019, p. 252).

Therefore, it is extremely crucial for a school’s climate and culture to be welcoming, accepting, and tolerant of all different identities and social groups in order for students to attend. Implementing in-class discussions or recognizing organizations that promote student unity, like the Gay-Straight Alliances (Burton et al., 2013, p.45) have been proven to build a stronger school community which will further encourage academic participation.

Mental Health: Individual Level

Another area of inquiry that is closely related to absenteeism is mental health. Mental health refers to changes in one’s mental well-being due to biological factors, life experiences or family health history. Adapted from the APA Dictionary of Psychology (2023), mental health is a state of mind characterized by emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life. According to a longitudinal study of 9 to 16-year-olds, 25% to 90% of those who missed school met the criteria for a diagnosis as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), whereas less than 7% of those who did not miss school met the criteria for a diagnosis. School refusal due to anxiety, unexcused or unexplained absence, and mixed school refusal behavior were the three types of absence.

The emphasis on maintaining good mental health should therefore be placed on students’ life experiences and how those experiences may have an impact on their behavior and academic performance (Jones et al., 2019). Otherwise, students will experience negative effects like truancy and self-neglect. While there are many environmental influences (school setting, home, etc.), mental health is a big determinant to high school absenteeism. There are studies that showcase how mental health affects more circumstances than others. For instance, Burton et al (2013) provides a study that examines the potential connection between school absenteeism and mental health as well as implications on SMY and heterosexual youth. They conducted a longitudinal study with a sample of 108 adolescents, including 29% males and 71% females and consisting of 26% (n=28) classified as a sexual minority. Concurrent with their predictions, they found correlations between absence variables, depression symptoms, and anxiety symptoms, especially being higher for SMY. This demonstrates how mental health should not be viewed solely through the lens of typical populations (i.e., heterosexual youth), and it inspires us to view mental health through a multidisciplinary lens, such as anxiety and depression.

For students, anxiety is a feeling that extends beyond worry or fear in a school setting. Rather, it is examining how these thoughts and interactions with these thoughts affect the spaces these students enter. For example, Jones et al (2019) reveal how anxiety has effects in a multitude of ways for children at the student, classroom, and district level. They utilized cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) based preventative programs as the main frame of analysis, attempting to prevent or treat anxiety disorders. They identified improvement in social competence, emotion regulation as well as reduction in emotion dysregulation, academics, and attendance. This reveals that mental health could be perceived better for the students if there were more examinations in the individual level (i.e. anxiety) within the macrosystem (i.e., mental health) (Signer, 2021).

The microsystem level also includes a student’s dating life, which can have a significant impact on the student’s mental health as well as the school’s culture. In this sense, dating violence may have a huge effect on high school students, especially at their age. The relationship between teenage dating violence and high school attendance among American pupils was recently investigated by Cheung et al in 2023. The results of this research show that high school students who had experienced adolescent dating violence (ADV) in the previous year had significantly higher chances of missing class out of fear than those who had not. The study also indicates queer students in non-heteronormative relationships are more likely to miss class. A previous study that compared the educational and psychosocial outcomes for SMY and heterosexual youth in grades 7 to 12 with a large school-based sample found that SMY had greater rates of self-reported truancy than heterosexual youth. (Poteat et al., 2011). In addition, homophobic victimization decreases school belonging and increases truancy in both SMY and heterosexual youth (Poteat et al., 2011), but the research was unable to fully explore the relationship between mental health and absenteeism.

Therefore, mental health and high school absenteeism should not be treated as mutually exclusive. Rather, critical examination of mental health in tandem with its tenets – such as, anxiety, depression, and dating violence – could offer an encompassing solution for high school absenteeism.

Solutions

Countless studies have tested various methods to combat high school absenteeism; whether it be solutions to be enacted by administrators, parents, or students. To start, administrators should begin looking into intervention practices. Intervention programs that involve increasing student and teacher relationships, and can impact other areas that need improvement. These areas would include attendance and parent involvement. The article by Eklund and Burns (2011) emphasizes teacher-student mentoring to help students’ problem-solving and coping skills. This article considers four categories of intervention, including behavioral, academic, family-school partnership and policy-oriented interventions. Across all four categories, the effect was small but positive on attendance intervention (Eklund et al., 2020). The authors argue for the involvement of parents in possible intervention programs.

Similarly, another program implemented to promote school attendance is called breakfast after-the-bell (BAB). Conducted in Colorado and Nevada, this study found that participation in BAB declined high school absenteeism and also found it beneficial to offer universal free meals (Kirksey et al., 2021). This form of intervention, targets the affect of food insecurity and eliminates the idea that students are not attending school because If students cannot get to school because of transportation and time management, operating as an incentive, free breakfast might motivate students to arrive earlier. It might also be easier for students to have transportation earlier in the morning rather than later.

Another solution is emphasizing the importance of a positive school climate. If the school does not have a positive school climate or is not a comfortable space, the students do not want to attend school. Werman et al., explain that students report not being able to hold difficult conversations in classrooms. This results in a negative school climate which leads to more absences. A study in 2020 by Nerveza-Clark emphasized how a positive school climate can lead to a more encouraging environment that students feel safe to attend. One way to create a positive school climate is by looking at the lanuage we use when talking about students that are absent. Schhol adminstartors and staff should change from deficit-based to asset-based language. Zinnen (2021) explains that asset-based language focuses emphasizes strengths. The phrase “chronic absenteeism” frames absenteeism as something that can not be fixed because it is persistent. This type of language does not promote positive parent-teacher relationships, which is important when working to increase attendance.

Analysis of Research Gaps

Although it is clear that there is an extensive body of literature surrounding high school absenteeism, there are many gaps in the research. For instance, given its recent existence, there is little literature which considers how the impact of the pandemic has affected school attendance. Furthermore, aside from the studies which aim to directly consider the pandemic’s impact, any studies that were performed after the dawn of the pandemic do not consider how its effects may have altered the results of the topic being studied, of which are unrelated to the pandemic (Chang et al., 2021). In other words, the pandemic is not acknowledged as a variable to have had an effect on the results of a study. Furthermore, there is limited literature found that specifically considers the city of Hartford and the factors which have led to this city’s high absenteeism rates. Although it can be speculated the reason for this lack of research around Hartford stems from the city’s small size, other highly credible sources performing research in lesser-known cities in other areas of the United States were found (Simons et al., 2010).

Another area of study to be considered in future research are the perspectives of the families of students with high rates of absenteeism. In current studies, when the role of the homelife is considered, it is only acknowledged as a risk factor affecting the student’s life (Ingul et al., 2013). Perhaps the familial perspective can offer unique insight into what the student’s life looks like outside the classroom and which factors of the student’s homelife may be contributing to their absenteeism. Similarly, there is a large gap in the literature that considers the perspective of the student with high rates of absenteeism. Few studies conduct interviews, focus groups, or other forms of qualitative data with students. Instead, studies acknowledging the student’s insight only do so through surveys (Burton et al., 2013) or examining statistical attendance data over a period of time (Kirksey et al., 2021), both of which are limited because they cannot gain the same comprehensive and robust responses that may be obtained through focus groups and interviews. Future research into these areas are crucial to discover concrete ways to dismantle absenteeism within Hartford and across the United States.

Conclusion

In conclusion, high school absenteeism is not a monolithic issue and should not be treated as such. Instead, it reveals how the environments of students could affect their emotional, mental, psychological, and social wellbeing, which in turn impacts their attendance rate. With the focus groups, it gives us an opportunity for community members to have a voice in this issue and improve education for the students. Although the literature covers public (i.e., community member participation) and private spheres (i.e., anxiety and depression), there were still gaps like the pandemic and families can be helpful toward building solutions for this issue. The preparation and finalization of this literature review have been a significant and collaborative learning experience. Below the research team has shared their thoughts.

“With the help of the literature review, we were reminded of the value of providing for the needs of the students, especially while keeping a critical eye on outside factors (such as work and family), viewing high school absenteeism from a multidisciplinary framework (such as the bioecological model), seeing this as a national issue, and adhering to readily available academic and mental health resources. In the end, the literature review process emphasizes how crucial it is to approach the issue holistically, taking into account the social, psychological, and environmental elements that influence high school absenteeism.”