The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Environmental Justice has long defined environmental justice as “the fair and equal treatment of all individuals, regardless of race, national origin, or income, and the protection of communities from disproportionate impacts of environmental hazards” (2013a). Neighborhoods labeled as environmental justice areas can include communities of color and/or low-income residents, who are frequently excluded from environmental policy and decision-making processes. These marginalized communities often face disproportionate exposure to industrial plants, waste facilities, and other environmental issues that negatively impact their quality of life and health, compared to higher income, white communities (American Public Health Association, 2025; Benson 2018; Holifield, 2013; Skelton & Miller, 2023).

Now a widely used term, environmental justice was first accepted by the federal government during the formation of the office of environmental justice under the presidency of George H.W. Bush in 1992 (Buford, 2017). The environmental justice movement, focusing on the health and safety of people of color, emerged in response to mainstream environmentalism’s exclusionary nature. The introduction of grassroots environmental justice movements challenged the traditional, resource conservation and wilderness preservation-focused ideas of environmentalism, expanding to address issues regarding race, class, culture, and civil rights (Holifield, 2013). Early environmental efforts from privileged, white elites excluded Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) residents from environmental policies, and even sought to exclude immigrants of color for “environmental purity” (Matsuoka & Raphael, 2024). As a way to combat this oppression, BIPOC grassroot organizations came together in an environmental justice movement to confront environmental threats in their neighborhoods, drawing inspiration from civil rights movements of Black, Latinx, Asian American, and Indigenous people. Environmental justice grassroots movements have regional networks, connected through local advocacy organizations that empower frontline communities with legal, technical, and financial support (Matsuoka & Raphael, 2024).

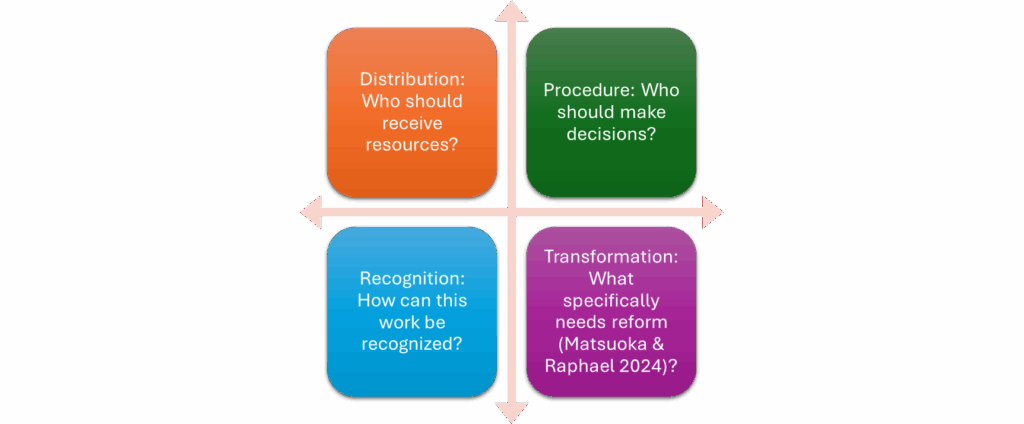

According to David Schlosberg’s influential framework of the “Dimensions of Environmental Justice” (2009), there are four levels of environmental justice activism:

- Distribution: Who should receive resources?

- Procedure: Who should make decisions?

- Recognition: How can this work be recognized?

- Transformation: What specifically needs reform (Matsuoka & Raphael 2024)?

Environmental justice is also categorized into four subsections known as the taxonomy of environmental justice:

- Distributive justice

- Procedural justice

- Corrective justice

- Social justice

This taxonomy offers a method to dissect the causes and solutions of environmental justice issues, with the ability to adapt to specific situations and positively enact change (Kuehn, 2004).

While there has been an increase in environmental justice movements and activism in recent years, many BIPOC communities are still facing environmental injustices, specifically exposure to hazardous waste. In 1987, the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ) conducted a study titled “Toxic Waste and Race in the United States,” finding that race, rather than income, was the most significant factor in determining the location of hazardous waste facilities. This national study was the first of its kind to systematically document the disproportionate placement of toxic facilities in communities of color, with the highest concentrations found in predominantly non-white neighborhoods (United Church of Christ’s Commision for Racial Justice, 1987). Hazardous waste facilities are intentionally placed near or in communities of color, since they do not have access to the resources that would allow them to oppose or fight back against environmental injustices (Matsuoka & Raphael, 2024). Additionally, centuries of racism, colonization, exploitation, and systemic oppression have impacted urban planning and decision-making in historically BIPOC communities (Matsuoka & Raphael, 2024). A combination of capitalism and environmental crises have made it difficult for people of color to obtain protection from hazards due to the federal government’s lack of services, investment, and urgency towards marginalized communities. Some older studies argue that environmental injustices and racism do not always coincide, referencing cases where both people of color and white people faced the same environmental injustices by living near hazardous industrial plants (Jeffreys, 1994). However, the CRJ’s study is widely accepted as clear evidence indicating the correlation between race, residence, and exposure to waste facilities.

Environmental racism, a term created by civil rights leader Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., centers around the question: “Which came first, the waste facilities or the poor communities of color?” (Ihejirika, 2023). Some studies attribute the disproportionate placing of hazardous waste facilities to market dynamics or lifestyle choices, stating that lower property values attract both industrial facilities and economically disadvantaged residents. However, further analysis is needed to assess whether these forces are themselves driven by unjust social practices, such as redlining, disinvestment, and discriminatory zoning, or if they stem from other structural or economic factors (Cole & Foster, 2001). Some claim that the study of environmental racism is framed through the lens of white privilege, relying heavily on empirical data instead of qualitative data from oral history interviews that center the voices of marginalized communities. In order to analyze issues of environmental justice and environmental racism, it is necessary to understand systemic and societal racism, rather than intentional discrimination towards BIPOC (Pulido, 2000).