- Why Our Methods?

- PhotoVoice Process Overview

- Data Collection and Analysis

- Oral History Interviews

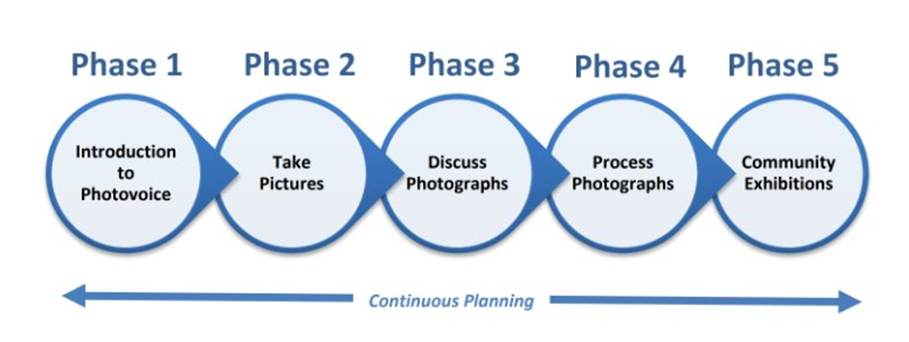

- PhotoVoice

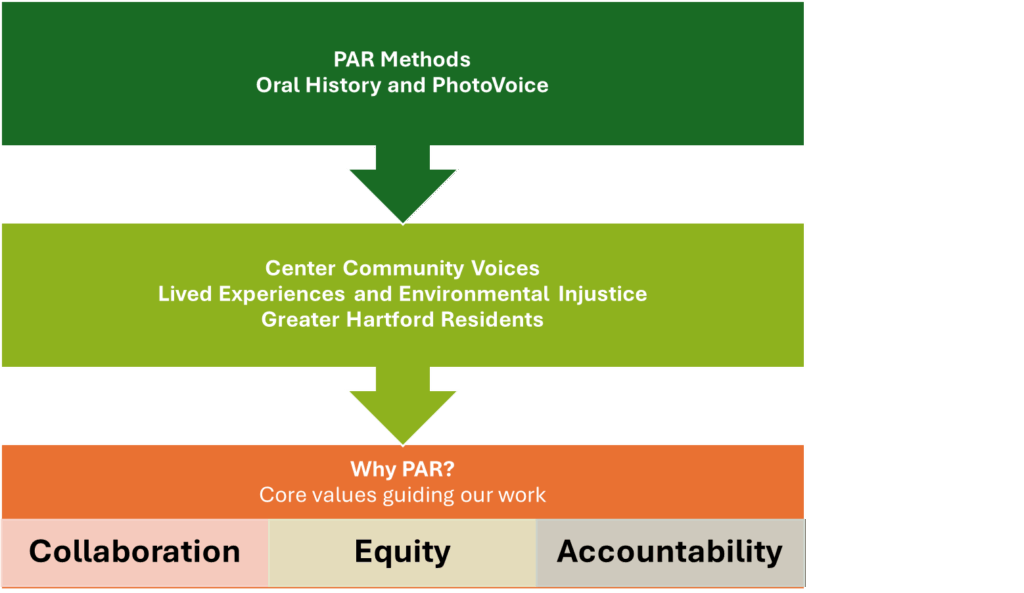

Why Our Methods?

Our research employs Oral History and PhotoVoice as two primary Participatory Action Research (PAR) methods to center the voices and lived experiences of Greater Hartford residents, especially those impacted by environmental injustice. We intentionally chose PAR methods because they align with our values of collaboration, equity, and community accountability. PAR is not just a method but a framework that challenges hierarchical models of research by positioning participants as co-researchers, rather than subjects. This approach allowed us to engage meaningfully with marginalized communities in Greater Hartford, focusing on themes of environmental justice and trash management. All research materials were co-created with our community partner, then reviewed and approved by the Trinity College Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Oral History

Oral history is a qualitative research method focused on recording and preserving personal narratives to deepen our understanding of historical and contemporary experiences. It is particularly valuable in documenting the lives and perspectives of individuals and communities that are often excluded from dominant historical accounts (Perks & Thomson, 2015; Yow, 2014). By centering lived experience and memory, oral history offers insight into how people make meaning of their environments, institutions, and social structures over time.

These interviews created space for reflective storytelling, allowing participants to trace connections between their lived realities and broader socio-political dynamics. The narratives gathered provided historical context and deepened our understanding of the structural and emotional dimensions of environmental inequity in the great Hartford area.

Moreover, scholars like Valerie Yow (2014) emphasize the ethical and dialogic nature of oral history, especially in participatory settings. When researchers and community members co-create knowledge, oral history becomes a democratizing tool—one that affirms personal narratives as valid forms of knowledge and as acts of resistance against silencing or erasure (Shopes, 2003).

PhotoVoice

We complemented oral history with PhotoVoice, a participatory visual methodology that empowers participants to document, reflect on, and share aspects of their environment through photography. Through PhotoVoice, community research participants receive photography training and are given an assignment to document a question relevant to their lives. After submitting photos, participants gather to identify themes across the images, selecting resonant photos and developing captions that tell their story (Gubrium & Harper, 2013). PhotoVoice prioritizes the individual’s ownership of their story and provides a platform for visual storytelling that centers lived experience.

“A decolonial and participatory visual storytelling approach, at the foundation of PhotoVoice is the individual’s ownership of their own story, particularly crucial for individuals who are often marginalized.” (Gubrium, 2013; Warner, 2020)

PhotoVoice was vital in ensuring that our data analysis remained grounded in the values, priorities, and perspectives of the community. By centering what participants find meaningful, PhotoVoice ensures that data analysis is rooted in lived experience, revealing the patterns and impacts that reflect community realities. Photovoice strives to analyze qualitative data that follows the priorities of the stakeholders. Through this methodology, our research gained invaluable qualitative data and insight into trash management and environmental justice in Greater Hartford, without the potential pitfalls of “traditional research methods. (Gonzalez, 2007).

PhotoVoice also served as a catalyst for dialogue, allowing stakeholders to guide the direction of conversations. In a research endeavor in La Ventanilla, Mexico, researcher and author Warner Wood details a dramatic shift in perspective he felt during his work. He would go on to state that they “would never have thought the situation would be so complex” had it not been for the opportunity to seek out and work through the priorities and concerns of the community through Photovoice (Warner, 84).

Data Collection And Analysis Methods

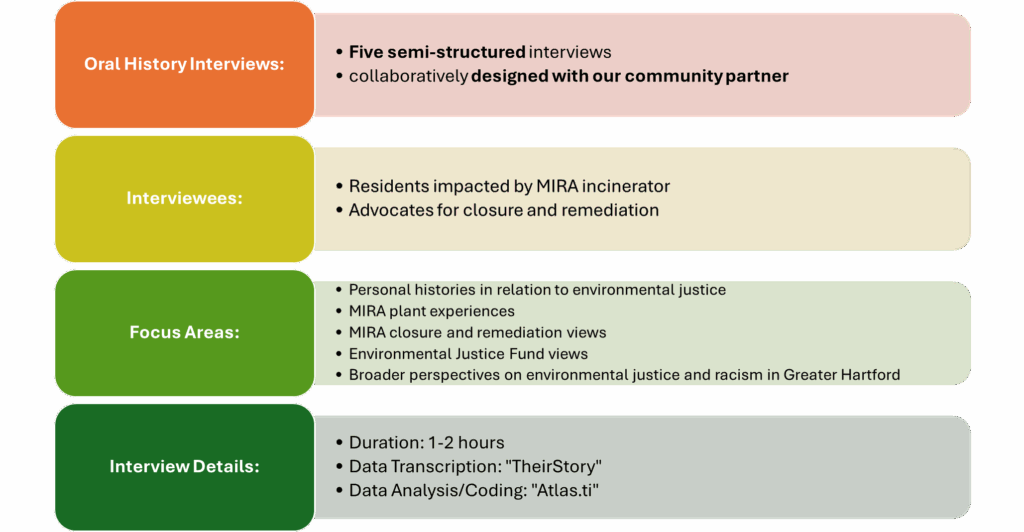

Oral History Interview

We conducted five oral history interviews with current and former South End residents impacted by the MIRA trash incinerator, and individuals involved in the plant’s closure and remediation process. After students received training in oral history methods and ethical research practices, participants were recruited by Sarah McCoy, a community organizer from Center for Leadership and Justice, and a co-instructor of this project. Participants were asked a series of questions about their experience with the MIRA plant or other environmental harms; views on the MIRA closure and remediation process, including the possibility of establishing an Environmental Justice Fund; and more general perspectives on environmental justice and racism in Greater Hartford. After each interview participants were invited to complete a brief demographic survey to self-identify their gender, race/ethnicity, and other characteristics.

Participants were offered the option to be identified with their names, or to remain anonymous. All five participants, listed below, chose to be identified.

Tom Swarr: Retired engineer, representative on the MIRA Dissolution Authority, and South End Hartford resident.

Diana Heymann: educator and activist involved in GHIAA organizing efforts across Greater Hartford, former Hartford resident.

Yahaira Escribano: grew up near the MIRA trash plant and faces related health impacts

Pedro Bermudez: filmmaker, Wesleyan professor, and long-time South End resident

Sister Patricia McKeon: Nun with Sisters of Mercy, Hartford South End resident, lifelong activist directly impacted by the MIRA plant.

Offering a broad range of experiences related to trash management and environmental justice in Hartford, our interviewees include residents impacted by the MIRA incinerator, advocates involved in its closure and remediation, and a former employee and member of the MIRA Dissolution Authority board. Interviews with advocates provide valuable insight into the intersecting opportunities and challenges of remediation. In a similar way, interviews with residents provide firsthand accounts of MIRA’s impact on public health, revealing the priorities of impacted residents. In total, three participants were from Hartford, while two were from West Hartford and Middletown. There were two male-identifying participants and three female-identifying participants, ranging in age from 29 to 83. Two of the participants were Hispanic or Latina, and the other three were White.

Averaging between one to two hours, interviews were recorded then transcribed using TheirStory, and analyzed/coded using Atlas.ti. On our first read through of the transcriptions, we extracted relevant themes. On the second read through, we identified specific statements that fell under these themes and added new themes. In our third read through, we further refined these themes and continued to code oral history responses.

PhotoVoice

For the PhotoVoice element of the project, we aimed to capture how trash management impacted residents of Hartford and its suburbs. Community partner and co-instructor Sarah McCoy of the Center for Leadership and Justice recruited seven participants from Hartford and surrounding towns who wished to share their experiences of trash management and environmental justice. Among the participants, six identified as women, five as Black or Latine, and two as white. They were primarily young adults, with four in their 20s. Participants could choose to be named or to keep their identities confidential; thus in the PhotoVoice findings section six of the seven participants are credited by name.

In early March 2025, participants received training in PhotoVoice methods and ethical practices and took part in an exemplar PhotoVoice exercise, including a walking tour of Hartford’s Constitution Plaza by public historian Steve Thornton. The training introduced the main PhotoVoice assignment, which asked participants to take five or more photos “of the trash management process in your community that you feel are significant.” As they took photos, participants were instructed to reflect on:

- How their household produces and manages trash

- How trash management impacts the health, safety, or quality of life of people in their community and surrounding communities

- How they think trash management impacts the health, safety, or quality of life of people outside their communities

- What they would like to change about trash management in Greater Hartford

Participants were introduced to a photo submission portal where they uploaded photos and provided captions and related reflections. Participants took a brief survey to self-identify their demographic characteristics. To end the training, they shared a dinner and discussion.

PhotoVoice Discussion:

After taking and submitting photos over a two-week period, on March 26, 2025, our research team and participants gathered at the Stowe Center for Literary Activism. The Stowe Center hosted a review of the photos submitted and facilitated a dialogue, allowing participants to identify the themes and images they found especially important.

Participants’ photos and captions were displayed on posters in Stowe’s visitor center. Participants were asked to circulate, annotating the posters to indicate how the photos made them “think or feel about trash management or environmental justice in Greater Hartford.” Thereafter, Stowe Center facilitators led a discussion focused on trash management impacts in Greater Hartford, views on MIRA and its closure, and hopes for its remediation, including the possibility of an Environmental Justice Fund.