Table of Contents

A Brief History of the Tenants’ Movement in the United States

Current Tenant Organizing Efforts across the US – Tenant Organizing Models of Today

Activism and Organizing in Hartford

Housing Assistance Programs

A Brief History of the Tenants’ Movement in the United States

From the late Nineteenth Century to mid Twentieth Century, tenant activism has been fundamentally found within the poor and working classes, being packed within slums linked to large industrial cities. Most early tenant organizations dealt with already existing issues within their own living units, being evictions, lack of heat, and unreasonable rent increases. With the offending landlords as the target of protest, local activists and organizations rallied for the widely sought conclusion of rent control, which was achieved and initiated in the 1920’s within New York’s urban housing areas through citywide groups organizing with trade unions, radical political groups and already elected officials (Dreier, 1984).

When the Great Depression ravaged working class communities in the 1930’s, tenant organizing was primarily grouped in major cities in collaboration with socialists and communists as part of the shared effort to politicize and industrialize industrial workers and the unemployed. As a result of their efforts, tenant and union activity became recognized and supported by elected officials and middle-class reformers. These two vital interest groups in organizing allowed the creation and conduction of studies on tenant space and slum conditions and rent rates of relevant and determining areas.

During and immediately after the U.S. involvement in the Second World War, various labor and protest groups unified “…behind the war effort and tempered their protests.” (Dreier, 1984 p.257). In result, Congress enacted federal rent controls, which was pulled in 1947 by the Truman Administration lifted the regulations as an attempt to create “…a postwar boom in home ownership” (Dreier, 1984, p.257), an unattainable goal by many industrial workers and members of the lower class.

Tenant activism remained on a consistent decline until the Harlem Rent Strikes in 1964, which triggered support for organizing nationwide. The strikes were effective in retaining media and political attention, involving “…more than 500 buildings and 15,000 tenants. They received nationwide attention and helped inspire tenant activism in other cities, primarily among low-income blacks” (Dreier, p. 257). Rapid organizing, activism and mobilization would, in result lead to the founding “…of the first nationwide group, the National Tenants’ Organization (N.T.O.)” (Dreier, p.257) which formed in 1969.

Tenant activism would regain momentum in the 1970’s through a series of factors that triggered mass organization. Firstly, much of the poor and lower middle class resorted to long-term leasing as a substitute for purchasing a home, which was and still is massively expensive. Low vacancy of housing units led renters to stay in the same homes and living spaces which would in result develop leaders and community organizers to form. Finally, outsourcing and the absence of landlords on the premises inhibited activism, citing the inactions and neglect of ‘absentee landlords’. These three key factors led to rent strikes, demonstrations, pickets and rallies to be a common response to either incompetent or offending landlords, calling for political support and litigation in protection of tenants and housing rights.

Today, we see modeled forms of activism and reasoning in Connecticut, demonstrating modernized models of organizing that were originally shaped nearly a century ago. Various tenant organizations have and are still operating in the CT Capital area in recent, including No More Slumlords, CT Tenants Union (CTTU) and a variety of others that have worked and advocated for equitable and fair housing, utilizing social, legal, and political resources to gain media attention and legislation (Monk and Vallejo, 2022).

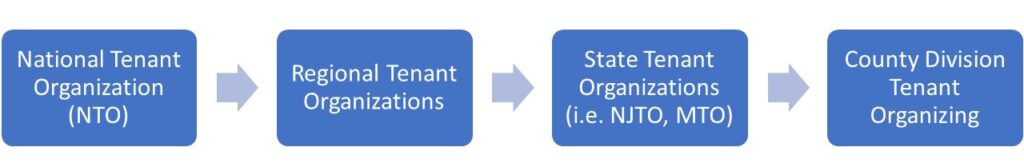

Tenant organizing at different scales

Local-level tenant organizing throughout the United States follow relatively identical models concerning means of operation. This is due to extensive oversight and overseeing by organizing promoters working at the national level such as the National Tenant Organization (N.T.O.). This form of direction allows regional or local institutions to address problems close to home in similar fashions that have proven to be beneficial to its members. Similar to unions operating in the United States such as the Massachusetts Tenant Organization (M.T.O.) and the New Jersey Tenant Organization (N.J.T.O.), other associations, namely ‘No More Slum Lords’, CTTU; have offered renters in community to Hartford legal resources to meet needs linking to justice and allows tenants to have a voice through media promotions (Monk and Vallejo, 2022).

Current Tenant Organizing Efforts across the US – Tenant Organizing Models of Today

- In New York, Housing Justice for All is a statewide movement of tenants and people experiencing homelessness aimed at positioning housing as a human right. Since its start as a grassroots community movement in 2017, the organization has pushed for stronger tenant protections to ensure housing stability. In 2019, New York passed sweeping renter protection laws that shifted power to tenants by closing loopholes that landlords had used to deregulate housing by raising rents. The impact of the legislation extended protections to 2.4 million renters in the state (https://housingjusticeforall.org/).

- In California, Housing Now CA is a power-building coalition with over 150 organizations and 1,000 grassroots leaders in its network. The group aims to make housing more affordable for working class communities of color and to combat displacement caused by large corporations and landlords. Housing Now CA works with a range of tenants, workers, and businesses to push for the passage of the California Tenant Protection Act, which prevents rent gouging and unfair evictions (https://www.housingnowca.org/).

- Tenant organizing in Boston has seen some inspiring examples. One notable organization is City Life/Vida Urbana, which has been at the forefront of fighting for tenant rights (https://www.clvu.org/). They have organized rent strikes, protests, and negotiations with landlords to prevent evictions and secure affordable housing. Another organization is the Boston Tenant Coalition, which brings together various tenant groups to advocate for policies that protect tenants and promote affordable housing (https://www.bostontenant.org/about/). These are just a couple of examples, but there are many more amazing tenant organizing efforts happening in Boston.

- Tenant organizing in Texas has also seen some impactful efforts. One prominent organization is the Texas Tenants’ Union, which provides resources, education, and support to tenants across the state (https://txtenants.org/about/). They help tenants understand their rights, navigate legal processes, and advocate for fair housing policies. Another example is the Austin Tenants Council, which offers counseling services, tenant education, and community organizing to empower tenants in the Austin area (https://texaslawhelp.org/directory/austin-tenants-council). These organizations work tirelessly to ensure that tenants’ voices are heard and their rights are protected.

Tenant organizing is not a phenomenon that is specific to Connecticut or the northeast region of our country. Across the US, tenants are recognizing that there is power in the collective and organizing to advocate for themselves.

Activism and Organizing in Hartford

Neighborhood Organizations, Hartford Source: Adapted from Simmons, 1994.

Over the course of its existence, Hartford’s economy has undergone numerous changes, and the city has faced numerous challenges (Walsh, 2015), a prominent one being its housing issues (Thornton, 2013). There were civil rights, local civic, and anti-poverty organizations that started in Hartford during the 1960s and 1970s, but it was not until the formation of the neighborhood organizations that real change started to happen. The first one of those was Hartford Areas Rally Together (HART), which was founded in 1975. HART focused on the southern half of the city. HART’s efforts inspired Organized North Easterners (ONE), which was a small community development organization, and Clay Hill and North End (CHANE 8), which came from local neighborhood groups and existed from 1979 until 1988, to merge and become ONE-CHANE. Later in 1983, Asylum Hill Organizing Project (AHOP) was formed (Simmons, 1994).

AHOP, just like HART, formed block clubs, was also involved with organizing tenants, incorporated a social service center into its program, and launched a housing development arm.

HART’s area has the largest share of the white population, and early on, HART mainly appealed to white homeowners. Eventually, they tried to set up an organization specifically for Hispanics (Vecinos Unidos), but after many issues, they merged back with HART. HART’s organizing methodology was setting up block clubs; an impressive team of organizers succeeded in setting up over thirty block clubs in the southern area of Hartford (Simmons, 1994). This same methodology would later be emulated by ONE-CHANE.

Connections with other Organizations

HART, AHOP, and ONE-CHANE are all part of a statewide network of neighborhood groups, United Connecticut Action for Neighborhoods (UCAN). UCAN provides assistance and supervision of organizing staff for its member organizations. These three organizations also participate in the National People’s Action (NPA), which is one of four national networks of organizations that use methodologies similar to those of Saul Alinsky. The other networks are ACORN (the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now), Citizen Action (related to the Midwest Academy and Heather Booth), and the Industrial Areas Foundation, which was originally founded by Alinsky.

UCAN Apprenticeship Program

UCAN helped start up multiple new organizations with its 6-month community organizing apprenticeship program for African American and Latino people, where they train them before letting them work with a community organization. Two of the groups that got started thanks to UCAN were United Seniors in Action and Connecticut Union of Disability Action Groups.

Strategies and Tactics

Although they still faced challenges from large corporations and ghost landlords, HART, AHOP, and ONE-CHANE were all fairly effective in bringing about change. Fortunately, they were able to break through the code and discover dependable strategies for persuading these powerful corporations to take action. To be able to fight against big corporations, these groups relied on unpredictability; in order to be most successful against large corporations, they had to constantly alter their strategy, making it impossible for the latter to plan ahead and respond in a timely manner. Among their tactics was to single out an individual, preferably someone with the power to make decisions, when going up against a large corporation such as a bank or in the absence of a specific landlord. They would use the media to raise awareness of their concerns and compel the large corporations to take action by making their voices louder.

There is no official archive of Hartford’s tenant organizing history, and because of that, most of it is fragmented. The book “Organizing in Hard Times: Labor and Neighborhoods in Hartford” by Louise Simmons is the closest thing we have to an archive. The first edition of it appeared on April 14, 1994. As a result, a great deal of history gets lost, and there is no true archive of it, which is why this study was required. The most well-known neighborhood organizations—HART, AHOP, and ONE-CHANE—as well as their tactics, beginnings, difficulties, and even the individuals who contributed to their success—are covered in great detail in this book.

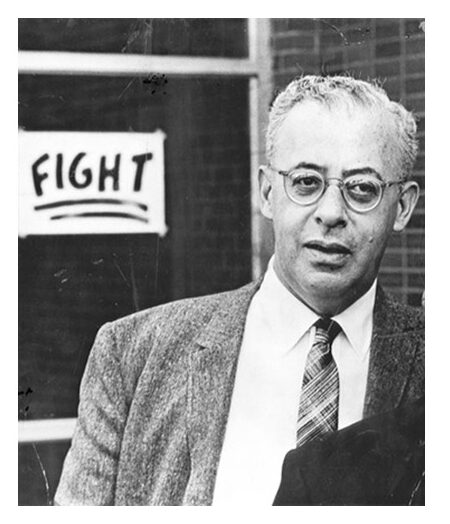

Saul Alinsky by Pierre869856 licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

“anger as a motivational tool” (Simmons, 1994)

Though he wasn’t directly associated with the organizations listed above, Saul Alinsky is credited as the founding father of community organizing because of his influence and strategies. His first guidebook, “Reveille for Radicals,” was published in 1946. He then developed “rules for radicals,” which were released in 1971, and both of these served as the model for numerous grassroots community organizations. Alinsky founded the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) in 1940, which is a network of neighborhood- or faith-based projects. It was then used as the model for future similar networks, including the Pacific Institute for Community Organizations, which John Baumann founded in 1972. His core beliefs were that the organization should not represent the people; rather, it should empower their voices. Rather than concentrating on achieving a particular objective, he thought that those who were not receiving enough attention should be given power and resources.

Housing Assistance Programs

Section 8 is a U.S. federal housing assistance program created in 1974. Administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, it provides rental subsidies to eligible low-income individuals and families. Participants receive vouchers to help cover the cost of renting privately owned housing. The voucher will cover the difference between the cost of rent, and however much 30% of the renter’s income covers. The program aims to make housing more affordable for vulnerable populations, preventing homelessness and promoting stability in communities. Despite facing challenges like funding limitations and the availability of affordable units, Section 8 remains a crucial tool in addressing housing insecurity (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development).

Connecticut’s Rental Assistance Program (RAP) is meant to supplement the shortcomings and accessibility of Section 8. Similarly, it functions to bridge the gap between an individual’s income and the cost of renting suitable housing.

The primary initiative of the federal government to aid low-income families, the elderly, and the disabled in securing decent, safe, and sanitary housing in the private market is the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program. By extending housing assistance on behalf of individuals or families, participants have the autonomy to select their housing, ranging from single-family homes and townhomes to apartments. Participants can freely choose any housing in the private market that aligns with the program’s requirements.

The Housing Authority of the City of Hartford (HACH) administers the voucher program using federal funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Families receiving housing vouchers are tasked with identifying a suitable housing unit of their choice, where the property owner agrees to participate in the program. This housing unit may encompass the family’s current residence. To meet health and safety standards established by the Housing Authority, rental units must adhere to specific criteria. The Housing Authority directly disburses a housing subsidy to the landlord on behalf of the participating family, who is then responsible for covering the variance between the actual rent charged by the landlord and the amount subsidized by the program (The Housing Authority of the City of Hartford).

Note: This is not an exhaustive list of housing related assistance programs. These are programs that are frequently mentioned by our interviewees and also came up during our research.