We have recognized that access to a comprehensive source of information on former tenant activism tactics is essential to providing a foundation for future efforts in Hartford. This source will hopefully facilitate and inform our community partner’s continuation of historical activism for housing rights in Hartford, as well as provide a jumping-off point for other organizations or individuals hoping to become involved. We are hoping that tenant advocates and organizers can use this project as a source of inspiration and a conduit to connect them to prior tenants’ advocates and organizers. We are hoping that residents, specifically tenants in our state, can see this information and be inspired to propel the tenant movement forward. To do this, we tapped into several different resources.

Canvassing at Woodland Village in the Asylum Hill neighborhood of Hartford on September 28, 2023 LAAL Housing Equity Team.

Data Collection

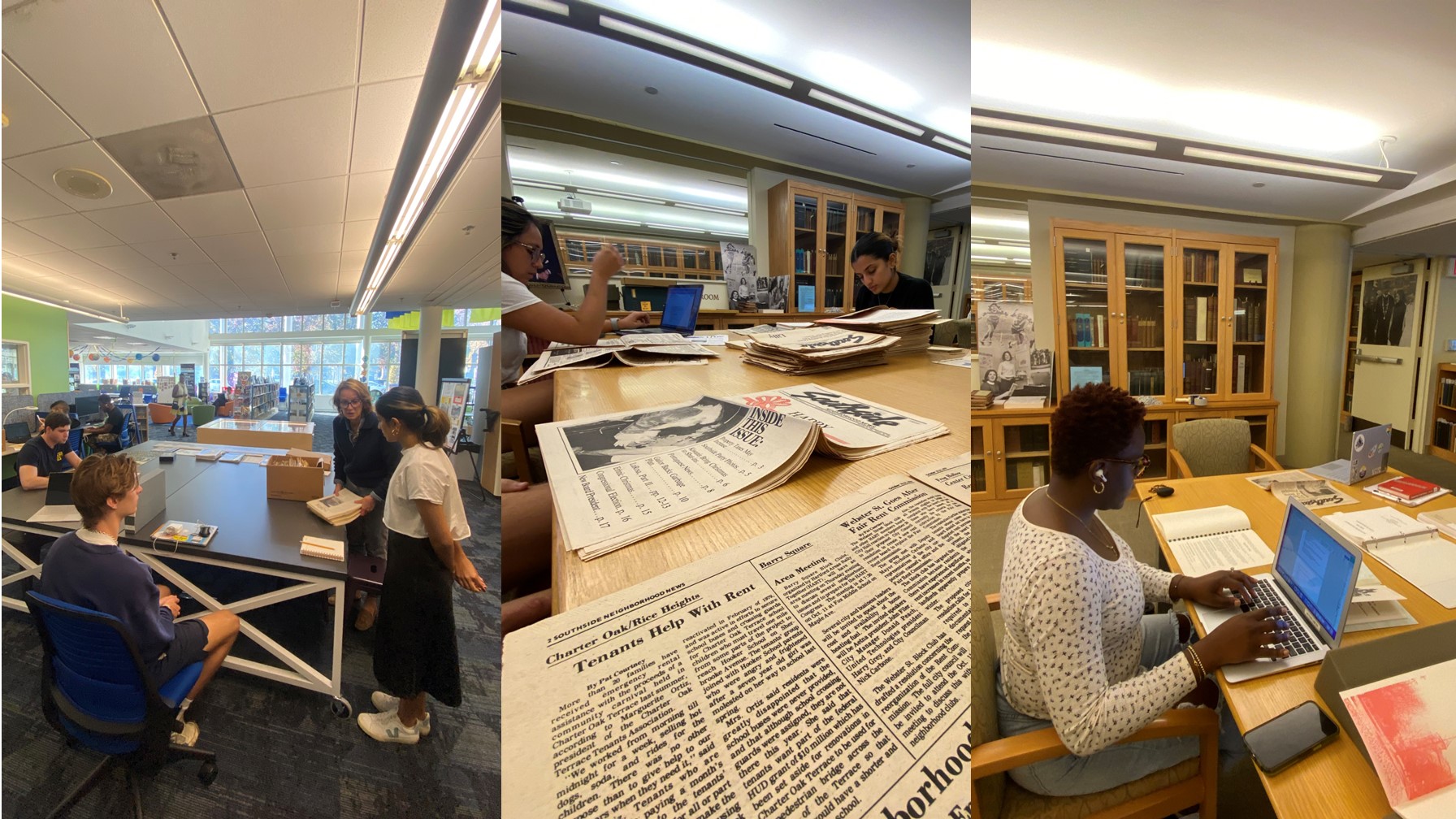

We utilized the online digital archives from the Hartford Courant between the years 1960-2000 and did numerous searches through Google Scholar using keywords such as ‘tenant movement’, ‘tenant organizing’, and ‘rent strikes’. We also did physical archival research at Watkinson Library at Trinity College and the Hartford History Center Branch of Hartford Public Library. Our methodology consisted of in-depth archival research, where we scanned newspaper websites, visited the aforementioned libraries, and checked public records on the Connecticut General Assembly website.

During data collection at Watkinson Library, Trinity College and Hartford History Center by Liberal Arts Action Lab Housing Equity Team

We also set aside time to meet with leads provided by our community partners for interviews. After those interviews, we asked our leads to provide us with contact information for individuals of interest that could contribute to this project. This method is called ‘snowball sampling’.

Snowball sampling is a method used in research to find participants for a study. It starts with a small group of people who meet certain criteria, and then those people help identify and recruit additional participants who also meet the criteria. It’s called “snowball” because the number of participants grows like a snowball rolling down a hill. This method is often used when it’s difficult to find participants through traditional sampling methods. We found this method most helpful with out research because it was difficult for us to research individuals involved in the tenant organizing movements of the past by just using the internet search engines. There are many individuals that may not have a public presenting persona, so asking people who we interviewed if they knew of anyone who would be interested in our project provided direct links to vital resources.

Our interviews for our oral history presentations generally lasted an hour, and the questions we asked our participants delved into biographical details, such as family history and where were they burned and raised and proximity to the tenant organizing movement. We were interested in what sparked their interest in organizing, and what successes and failures they faced in their journeys. Most of our interviews happened via Zoom for the sake of convenience and ease of transcription.

We also gathered secondary data on housing-related indicators such as tenure status and rent-to-income ratio to give context for Hartford, CT utilizing American Community Survey datasets and CT Data datasets.

Data Analysis

We have coded and organized a written and oral history of tenant unions in Hartford on a website, which serves as our final product. We incorporated our interview audio along with written transcripts, so individuals are able to immerse themselves in the exhibits. We have developed a list of contact people that individuals can reach out to in order to learn more about the work. This, however, is not a complete list of all tenant organizations within the state, but a start to work that we hope will continue to grow and take on a life of its own.

We diligently followed a meticulous data analysis process, which involved transcribing the audio files from our oral history interviews. To accomplish this task, we utilized the efficient transcription services of Otter.ai and Trinity College’s transcription software. We made the necessary revisions to ensure the accuracy of the interviews. We carefully coded our data from the interviews, in addition to the archival data we collected. We employed a combination of deductive and inductive coding techniques to categorize every item in each collection. Throughout this process, we had established certain codes like ‘housing struggles’ and ‘organizing challenges’. However, we recognized the importance of incorporating new codes that arose from our data. Stories of resistance have emerged from our research, which we believe are crucial to emphasize. We organized our archival materials into collections in Omeka, allowing us to create captivating thematic exhibits that take audiences on a spatiotemporal journey. This website effectively showcases housing related issues, organizing strategies, and stories of resistance.

While gathering research for this project, our community partner the Connecticut Fair Housing Center invited us to join them in canvassing efforts in the Asylum Hill neighborhood of Hartford. In meeting with the residents of Woodland Village Townhouses, we were able to gather first-hand accounts of the unjust conditions being faced by the tenants living there. One of the main issues arose from the lack of a landlord present. Absentee or non-responsive landlords have been highly prevalent in this case and many others across the state. By not having a local landlord, tenants are disadvantaged because they don’t have a clear pipeline of where and how to report issues on the property. Corporations coming in and buying properties have caused the rise in absentee landlords, leaving tenants to struggle when trying to find someone to hold accountable. Furthermore, tenants reported that the units suffered from poor maintenance. The buildings housing the units were in disrepair, and many tenants complained of requesting for things to be fixed but not getting a response, or getting a response years after an initial request was made. Many tenants had to deal with the issues on their own due to the presence of rodents and roaches and the lack of a clear way to contact a landlord. One tenant, in particular, had cats to try to combat the rodent infestation she was facing. The tenants are facing a plethora of other issues, including problems with heating and AC, health concerns such as mold, and unattended and ill-maintained parking, which has the possibility to cause accessibility issues for those residents who may be disabled. This instance is one in which the need for tenant organization is apparent. This field trip guided us in terms of developing our initial codes for our analysis.

Limitations

When it comes to research projects, there can be a few limitations to be aware of . Some limitations that we ran into are the fact that could not do a systematic review of archives by all the years available. The vastness of this project, the information and our limited resources as six students who are also enrolled in other classes led to us not being able to explore every archive in as great detail as we would have liked. We also had a list of about 20 potential interviewees. Despite our best efforts, it wasn’t possible for us to engage with each one. There were time constraints and also we were unable to reach some people due to outdated contact information. It’s important to acknowledge these limitations and consider their potential impact on the findings. But we don’t see these limitations as a bad thing. We acknowledge that limitations are a normal part of research and hope that they lead to new avenues of exploration for future groups.