What is the Culinary Career Pathways Model?

“…no one is born a great cook, one learns by doing.”

― My Life in France

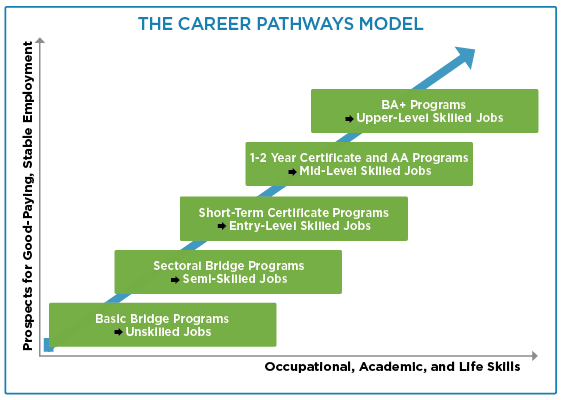

In a February 2018 report prepared for the United States Department of Labor, Maureen Sarna and Julie Strawn explain how the Career Pathways Model was developed to replace earlier job training programs; earlier initiatives had neither helped trainees escape poverty nor advance in a career. 1 As the American labor market evolves, it increasingly rewards and even mandates post-secondary credentials. Previous job training models emphasized quick job placement over credentials; these programs were only helpful to trainees in the short run, at best.

The Career Pathways Model progresses through a logical sequence of increasingly rigorous credentials that allow individuals to hop on or off the track at any point with a credential that should lead to a better job. The following diagram illustrates what the Career Pathways Model looks like:

So far, Career Pathways Models have been particularly successful in manufacturing and in health care fields, where a mixture of entry-level, mid-level, and upper-level jobs abound. Applying the Career Pathways Model to the culinary field has proven more difficult. America’s demand for culinary training is nothing new: as Jeffrey N. Brown reports, a European-taught chef named Charles Ranhoffer made one of the earliest calls for culinary training in 1898. 2 Nowadays, America’s culinary education system stresses “a broad knowledge of foodservice industry history, with an appreciation of current trends in culinary education.” 3 Thanks to the efforts of the late Julia Child and other celebrity chefs, some people think that being a chef from an accredited culinary school is all there is to the profession: the reality is that going to culinary school is not essential “if your goal is to be the food and beverage director at a hospitality brand, or working as a sous chef.” 4 One does not need to go to a prestigious culinary institute to make a living, but partially as a result of misconceptions, there has yet to be a pipeline, in the same way, there is for the STEM fields. The annual median pay for waiters and waitresses—a profession which requires no formal training—in 2018 was $21,780. 5 The annual median pay for food and beverage serving and related workers—which also requires no formal training—is only slightly less, at $21,750. 6 However, as restaurant cooks are formally-trained, their annual median pay for 2018 is higher—at $25,200. 7

Community colleges offer an excellent alternative for secondary school graduates who wish for a culinary career and do not plan on attending university; financially, community colleges are much less expensive than full-time private universities and provide needed credentials to start a culinary career (as the above diagram demonstrates). According to a fact-sheet from our Hartford-based partner, Billings Forge Community Works:

Entry-level workers in the food industry can expect to start as food and beverage serving workers (median wages $11.48/hour in Hartford) and food preparation workers ($11.82), and fairly quickly move up to cooks ($16.27), institutional cook ($18.27), restaurant cook ($13.26), short order cook ($16.29), or first line supervisors of food workers ($14.30). 8

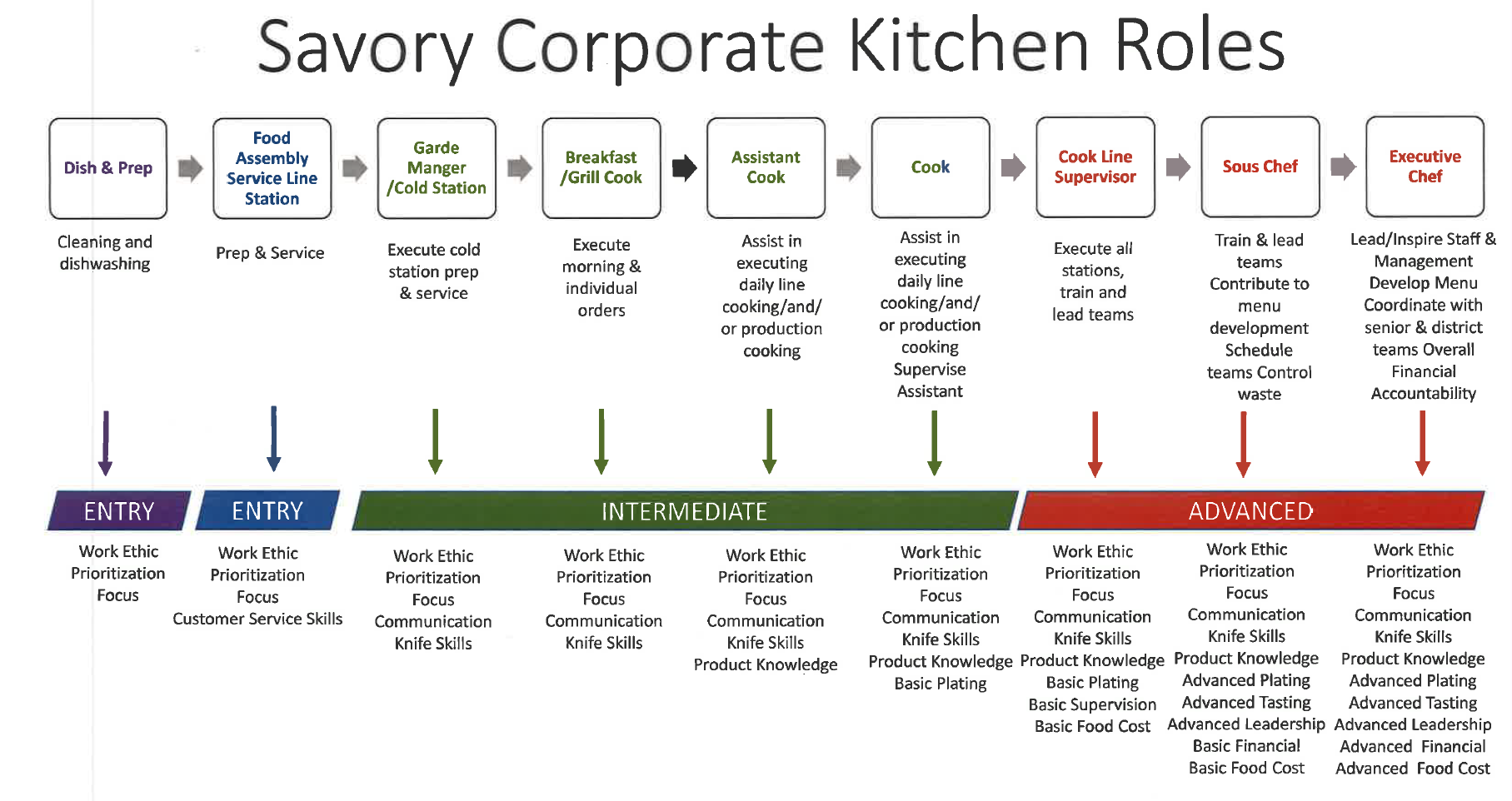

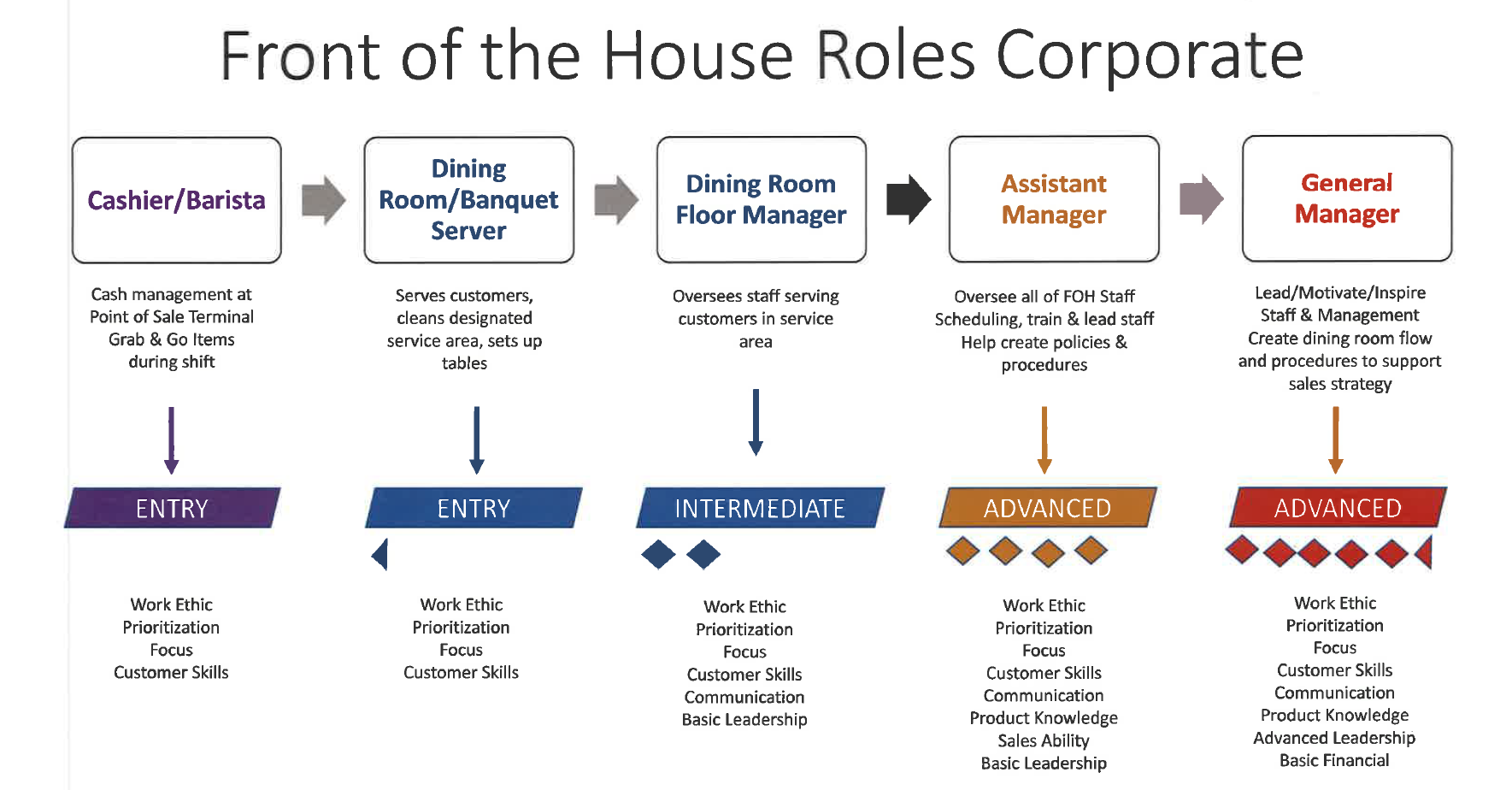

Evidently, there is an abundance of entry-level positions that do not require formal training to obtain and succeed. The following diagrams illustrate the progression of “back of the house” and “front of the house” roles for industrial corporate cafeterias.

Investment in trained employees helps save costs, and pay for themselves. 9 Jobs programs that work to introduce people with barriers to employment to paid work found the culinary industry is a good starting point.

- Maureen Sarna and Julie Strawn, rep., Career Pathways Implementation Synthesis (U. S. Department of Labor, February 2018), 1. https://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/completed-studies/Career-Pathways-Design-Study/3-Career-Pathways-Implementation-Synthesis.pdf.

- Jeffrey N. Brown, “A Brief History of Culinary Arts Education in America,” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education 17, no. 4 (2005): 50.

- Ibid., 52.

- Gowri Chandra, “Is Culinary School Still Worth It? Four Chefs Weigh In,” Food & Wine (Meredith Corporation, March 25, 2019), https://www.foodandwine.com/lifestyle/culinary-school-worth-it-four-chefs-weigh-in.

- “Waiters and Waitresses: Occupational Outlook Handbook.” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 12, 2019), https://www.bls.gov/ooh/food-preparation-and-serving/waiters-and-waitresses.htm.

- “Food and Beverage Serving and Related Workers: Occupational Outlook Handbook.” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 12, 2019), https://www.bls.gov/ooh/food-preparation-and-serving/food-and-beverage-serving-and-related-workers.htm.

- “Cooks: Occupational Outlook Handbook.” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 12, 2019), https://www.bls.gov/ooh/food-preparation-and-serving/cooks.htm.

- “Job Prospects for Culinary Work.” (Hartford, CT: Billings Forge Community Works, November 2018), 1.

- “Reduce Restaurant Labor Costs with These 7 Tips,” The Restaurant Times (POSist, October 10, 2016), https://www.posist.com/restaurant-times/editors-pick/7-lesser-known-ways-to-reduce-labour-costs-in-the-restaurant-business.html.