Literature Review

Table of Contents

Introduction

Theoretical framework

Key components of culturally responsive afterschool programs

Discussion

Areas for future research

Conclusion

Sowing Seeds of Affirmation: Reconceptualizing Afterschool Programming Using A Culturally Responsive Framework

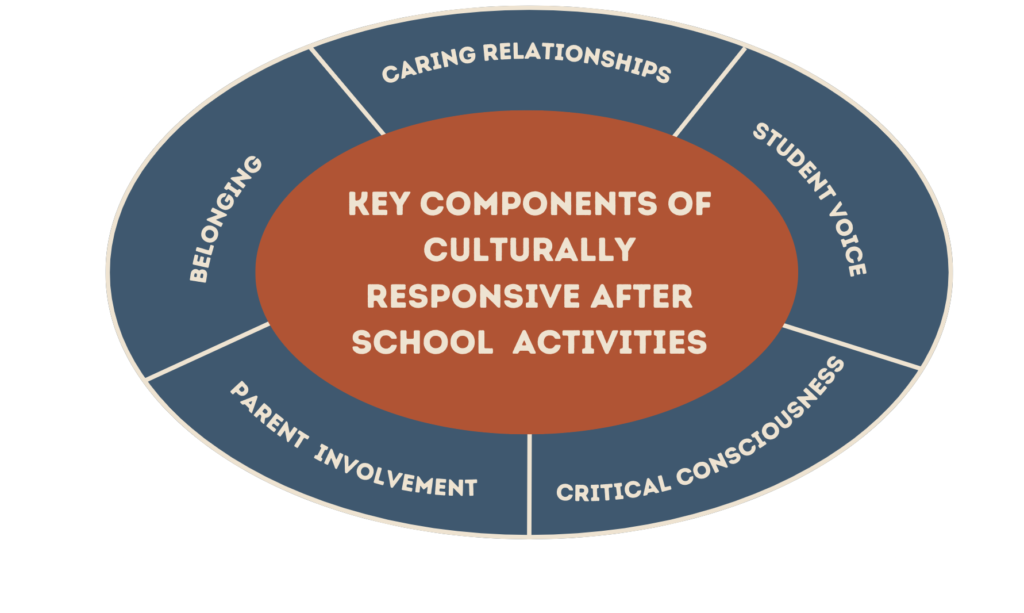

ABSTRACT: When constructed critically, culturally responsive afterschool activities have the potential to holistically improve marginalized students’ outcomes and provide youth with a space to belong and connect culturally. For Black and Brown students, after school activities can act as a haven of affirmation and support for youth who are too often criminalized in their educational system. For LGBTQ+ youth and women, afterschool activities can serve as an opportunity to amplify student voices in a welcoming social environment, allowing students a place to take pride in the diverse experiences that represent their self-identity and the communities they belong to in and outside of the classroom. Furthermore, our review of the literature reveals that afterschool program involvement is associated with stronger academic and behavioral outcomes for minoritized youth. We also found that afterschool programs that employ practices of cultural responsiveness are particularly effective at creating hubs of relational support. We assert that robust culturally responsive afterschool programs for marginalized youth are grounded in the following tenets: caring relationships, belonging, student voice, activism and parent involvement. These findings have implications for educators, youth, parents, and employees of afterschool spaces with Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, and women student participants.

Introduction

Strong culturally-responsive afterschool activities have the potential to transform youths’ lives. Research suggests that, when executed effectively, afterschool programming enhances positive development. High-quality afterschool programming provides students with a caring and accepting community, which is central to healthy youth development (Mahoney et al. 2009). Moreover, culturally-responsive afterschool organizations can subvert the eurocentric educational model too-often adopted by United States schools and provide avenues for students to explore their own cultural identity (Jackson 2022). Unlike traditional school lessons on nonwhite cultures–where narratives of Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, and women communities are pushed to the periphery, distorted, or oversimplified (Daniels 2021) –afterschool programs have the opportunity to engage in cultural excavation thoroughly and thoughtfully.

With the passage of Connecticut House Bill 5001 (An Act Concerning Children’s Mental Health 2022), afterschool programs can expect an influx in government funding. Introduced by the Public Health Committee, the legislation was passed with the purpose to “improve the availability and provision of mental health, behavioral health and substance abuse disorder treatments to children” (Connecticut General Assembly). For afterschool programs that are too-often stretched thin, this financial support has the potential to provide much-needed material support and expand organizational capacity. This renewed capacity provides the ideal opportunity for afterschool programs in Connecticut to critically reflect on existing curriculum for youth and develop new programs to meet the adapting cultural needs of the students they serve. In this pivotal moment, Connecticut’s afterschool organizations have the resources and responsibility to transform their cultural curriculum to support marginalized students and their intersecting identities (Simpkins & Riggs 2014).

Cultural responsiveness

According to Geneva Gay, who first popularized the term cultural responsiveness in 2000, cultural responsive teaching is defined as the use of “cultural characteristics, experiences and and perspectives of ethnically diverse students as conduits for teaching them more effectively.” Gay’s pedagogical model diverges from previously popularized frameworks for urban education in that it espouses an assets-based approach. Black and Brown culture, Gay asserts, has intrinsic value that can be built upon to engage and motivate students of color in the classroom. Research suggests that when culturally responsive pedagogical practices are used, class attendance, performance, and undergraduate prospects increase substantially (Howard & Terry 2011). There is a common theme, across much of the literature, of Black and Brown students feeling detached from learning due to eurocentric education models (Howard & Terry 2011). When culturally responsive frameworks are employed, students of all races, sex, and other cultural backgrounds have the opportunity to situate themselves within their learning, which is critical to fostering youth engagement.

Stiler and Allen (2014) explored the efficacy of culturally responsive education through a case study at the Carver Community Center. As Stiler and Allen discuss, the community center held a 3 month enrichment program for children that incorporated learning about African American traditions and folk art. The objective of this curriculum was to enhance self esteem and promote academic achievement through afterschool tutoring and cultural activities. Findings revealed that with the cultural curriculum, students were able to interpret events and artifacts on a deep level and gain understanding of and respect for their cultural heritage. Participating youth reported an increased interest in discussing African-American traditions at home as a result of this program. Researchers concluded that in the duration of this 3-month period, activities such as music, storytelling, and class discussions had advanced youth learning on African-American history and assisted in positive identity development. Though this program operated for only a short window of time, findings reveal promising results for the efficacy of culturally responsive after-school culturally responsive programs.

Another successful model of culturally responsive programming is the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School program (Gebretensae & Hornstein 2019). Directed by Tufts University, the program for three to five year-old children focuses on the four core themes: identity, diversity, justice, and activism. All children, staff, and family members are invited into the culturally inclusive environment created by the space, where the program seeks to provide a sense of security and identity affirmation. This anti-bias education adopts a holistic model of youth care and supports both the family and children to develop positive cultural identities. Education on gender expression is also incorporated into programming to encourage the development of a healthy gender identity by explicitly affirming diverse understandings of gender. Moreover, participating youth engaged in leadership activities to further advance their communication skills. The practices of the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School Program have been found to help prepare students for future academic success and cultivate an inclusive learning environment for youth of all backgrounds.

Afterschool activities

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, “afterschool programs (sometimes called OST or Out-of-School Time Programs) are school or community-based programs that offer academic and enrichment activities in the hours that follow the school day” (Supporting Student Success Through Afterschool Programs 2022). Afterschool programs vary greatly in content and structure, and often include academic support, arts engagement, sports and mentorship, among other activities. Programs that emphasize these fundamentals have become a central fixture of the youth care landscape, as over 10.2 million students participate in afterschool programs in the United States alone (Afterschool Programs).

Research suggests that one of the most critical dimensions of afterschool programming is the physical space itself. According to Rhodes and Schechter’s 2014 research on the Artists’ Collective in Hartford, CT (discussed in greater detail in the Theoretical Framework section), community-based youth programs provide students physical and psychological safety by providing an affirming, nonviolent space. The creation of youth community spaces is particularly significant for students navigating violence at school, in the neighborhood or at home, as afterschool programs may serve as the only environment for them to experience the security that is essential to positive development (Frazer-Thomas et al. 2005). In carving out space for youth to exist outside of the violence that so often surrounds them, afterschool activities help lay the foundation of safety that is essential to well-being and growth.

Despite often being overlooked in discussions about youth development, there is a robust body of research that suggests that afterschool programs are strongly associated with numerous measures of positive youth outcomes. Hurd and Deutch concluded in their analysis of the SEL campaign, an initiative for social and emotionally focused learning for diverse youth, that student engagement in afterschool programs that emphasize teachings of empathy, confidence building, and positive social norms learning has been positively correlated with positive perceptions of education, prosocial behavior, and improvements in self-confidence and self-worth (2017). Students who engage in afterschool programs have also been found to have higher rates of attendance and social-emotional skills and lower rates of problem behavior and school drop-out (Supporting Student Success Through Afterschool Programs 2022).

Afterschool activities and the achievement gap

Afterschool activities that incorporate cultural responsiveness into their curriculum are associated with an abundance of positive outcomes, including the increase in student achievement. Research suggests that children, particularly Black and Brown populations, who do not engage in consistent, culturally affirmative learning are disadvantaged as they struggle to develop the developmental skills needed to address their academics, behavior, and psychological needs (Fredricks 2008). While education experts recognize that such well-presented afterschool activities alone often do not distribute sufficient resources to reverse the economic, social, and systemic structures that undermine students’ best educational efforts, they find that participation in organized, culturally constructive exercises is associated with increased educational engagement and decreased rates of cheating, truancy, and interest in cigarettes (Anderson-Butcher 2003). Thus, in serving as an outlet for academic and interpersonal gains, culturally grounded afterschool events simultaneously function to challenge the oppressive operations that hinder students from achieving their goals, becoming leaders within their greater communities, and thinking critically about their futures.

While society traditionally tends to relate substantial student achievement with high grades and conventionally-esteemed career positions, a culturally responsive afterschool programming curriculum helps produce a diverse number of positive outcomes for youth. According to research supporting the multi-site initiative, Communities Organizing Resources to Advance Learning (CORAL), culturally constructive activities expose students to useful literary techniques, building a relationship between consistent afterschool programming and better reading and writing scores for students on standardized tests (Albreton 2010). Furthermore, research indicates that as students improve their academic performance, they become motivated to learn about new subjects and different experiences from the outside world, encouraging them to participate in sociopolitical processes and to apply critical thinking to local and global issues (Jennings 2006). This sense of inspiration drives student success in several aspects. By allowing students a place to practice cultural responsiveness, youth begin to think about their futures at a young age, laying a foundation for empathy and mindfulness as they make decisions, engage in school, and interact with different community members (Calhoun-Butts and Perry 2012). For instance, Daud and Carruthers conducted individual interviews and informal focus groups with students and staff organizers of afterschool programs that maintained culturally constructive instruction as guided by three community agencies: Afterschool All-Stars, 21st Century Community Learning Centers, and GEAR UP. In the study, 78% of participants reported that they started to think positively about their futures as a result of attending the afterschool events studied (Daud and Carruthers 2008). Therefore, normalizing cultural awareness in regular afterschool activities not only excites students into planning their futures but empowers them to achieve excellence as agents of change; contributing to their ability to lead discussions surrounding diversity and inclusion in a society that depends on robust leadership and intellectuals who can facilitate progressive social action (White 2019).

Theoretical framework

Youth resilience theory

It has become a common trope to label young people in urban environments with the pejorative marker “at-risk youth.” Used over time, this term has become associated with a deficit-based approach that seeks to alleviate community challenges by drawing on outside resources. This undermines the organizational, cultural, and epistemological assets of the community. This is not to say that urban communities cannot be distressed or that they are perfect–Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, and women city communities have been structurally oppressed and impoverished– but it is to say that the notion that they are devoid of their own resources is inappropriate and unhelpful. However, Youth Resilience Theory, as outlined in Schecter’s Fostering Resilience Among Youth in Inner City Community Arts Centers: The Case of the Artists Collective. Education and Urban Society, identifies the myriad of intra-community resources that can be drawn upon to cultivate youth resilience to the troublesome factors in their community. Resilience, put simply, can be defined as the ability for individuals to overcome experiences of trauma and extreme stress (Khanlou and Wray 2014). According to Schechter and Rhodes, the three components of community centers that can cultivate resilience are physical spaces, prosocial relationships, and the arts. Physical spaces are the spaces that youth are in, observe and engage with that have great potential to reflect the cultures, ethnicities, and local communities of the students. Prosocial relationships are the student-centered relationships formed within the spaces that students learn and live in that make them feel safe; when the students have guardians that make them feel welcomed and connected, they are more likely to share things about themselves and have better experiences. The arts are another venue that allow students to have a moment of reflection while also expressing themselves in an artistic manner; youth are able to create something beautiful that can reflect something troubling them or even a point of joy in their life. When implemented together, these tenets of community-based youth organizations may allow students to overcome the chronic stressors of structural racism and poverty to thrive.

Bonding and bridging

Bridging and bonding are the alliterative pairing that create a two-pronged theory that pertain to multicultural communities (Ahn 2012). Titularly, multicultural communities have more than one culture, and therefore, often have divides between these cultures that are not always beneficial for them or the communities at large. Furthermore, these cultures, minority cultures in urban centers in particular, are often marginalized thus are more likely to experience significant stress. Therefore, bonding with people of the same culture and creating community builds resilience from environmental factors and offers an effective coping mechanism against the aforementioned mental struggles. Bridging does the opposite but achieves a similar outcome; bridging forms connections and inroads across cultural lines that foster an environment for a positive multicultural community, rather than one divided. When a community is unified by common struggles and joys, they are able to create a space that is welcoming while also collectively resisting some of the stigmas that are associated with marginalized communities. When bridging and bonding are done in tandem, they create strong cultures and strong communities that dull the blades cut through and harm urban communities.

Key components of culturally responsive programming for afterschool community-based activities

Caring relationships

One emergent trend in robust culturally responsive afterschool programming is an emphasis on cultivating caring relationships. Cultivating relationships bound by care appears to be especially critical in adult-youth relationships in afterschool programs. Successful adult-youth relationships were found to be characterized by caringness (in addition to openness and positive challenges) (O’Donoghue et al. 2007). Moreover, students who had a caring relationship with an adult in their afterschool program were more likely to report that the program engages student voices and identify benefits to participation (Serido et al 2009, O’Donoghue et al 2007). Thus, creating adult-youth relationships can act as an avenue for student feedback and engagement in planning program activities. Interestingly, caring relationships between youth and adults can also catalyze students to foster their own sense of agency (Ventura 2017). In this sense, caring adult-youth relationships do not disempower students or increase youth dependency, but instead encourage youth to find their own voice. Beyond developing youth agency, promoting caring relationships within afterschool programs is critical to strengthening youth social consciousness. Caring adult-youth connections, then, act as the foundation for which students can build upon to foster social change (Ventura 2018). While there is significant convergence in the research on the importance of adult-youth relationships in cultivating student voice, agency, and social consciousness, information on the role of caring peer relationships in advancing student outcomes was difficult to find in the literature, and is an area for further investigation. Especially for non-mentorship afterschool programs like the Boys and Girls Club of America, understanding the impact of caring peer relationships–as well as the steps to take to develop them–is an area for further research.

Community of belonging

Beyond developing caring adult-youth relationships, research suggests that cultivating a community of inclusion and safety is critical to creating a robust cultural curriculum for afterschool activities (Jennings et al. 2006). For students of minoritized identities, educational spaces can be fraught with feelings of exclusion and disaffirmation (Ventura 2018). Black and Brown youth are often criminalized and marginalized in their academic environments (Khalifa 2013). Because of this, afterschool programs have the unique opportunity–and responsibility–to envelop students in a culturally responsive community of acceptance. In Ventura’s research on youth-led Latinx afterschool spaces, she found that creating a space of belonging allowed students to realize that their academic struggles were a shared experience of educational injustice, rather than a personal failing (2018). Research on the Artists’ Collective in Hartford also emphasized how creating an inclusive environment visually is critical to cultivating safe spaces. According to Rhodes and Schechter, the Artists’ Collective space displayed positive images of Black and Brown youth as well as art created by people of color to communicate belonging (2014). In addition to promoting a sense of youth solidarity, belonging in afterschool activities has also been positively associated with consistent and long-term youth participation. Thus, centering belonging in afterschool programming may also be an effective tool to address low rates of sustained youth engagement.

Student voice

Building a strong culturally responsive afterschool curriculum also requires the development of student voice in programming (Serido et al. 2009, Fredricks & Sampkins 2012). Student voice in afterschool programming can be thought of as the inclusion of students in curriculum creation, particularly cultural curriculum (Simpkins et al. 2017). In this sense, afterschool programs that successfully cultivate student voice encourage a dialectic construction of curriculum that shares decision-making power with youth. For this reason, it is unsurprising that research suggests that adult-youth power sharing is critical to program success (Jennings et al. 2006, O’Donoghue et al 2007). For afterschool organizations seeking to foster youth voice, it is therefore essential that adult-youth relationships be grounded in mutual respect and equitable decision-making power. While student-led afterschool programs have the potential to empower students to develop their voice (Ventura 2017), adult-youth relationships, too, can be an avenue for the promotion of youth voice. In fact, building healthy youth-adult relationships can facilitate the flow of student feedback to shape cultural curriculum (Fredricks & Simpkins 2012). Moreover, research suggests that students who had robust relationships with program adults were more likely to report that the program engages student voice (Serido et al. 2009). For marginalized students embedded in systems of oppression that silence them, afterschool programs have the opportunity to be a subversive force for empowerment in youth’s lives (Ventura 2017). When engaged critically, students can contribute meaningful feedback and ideas to curriculum–cultural or otherwise–at afterschool programs (Ventura 2017).

Critical consciousness and activism

When students are able to participate in the construction of their afterschool community space, they develop skills necessary in developing critical consciousness (Freire 2000). Ginwright and Cammarota (2002) propose that the development of critical consciousness and youth activism occur as students engage in three spheres of awareness: Self-awareness, in which they explore their relationality to power alongside their own identity; Social awareness, in which they discuss and analyze systems of domination; and Global awareness, in which they study structures of persecution internationally. Youth self-determination–which is promoted by the inclusion of student voice in curriculum creation–underlies social action, as it encourages students to subvert the status quo of injustice and organize for a different world (Ventura 2017). The development of critical consciousness is central to robust culturally responsive afterschool programs, as it provides (often marginalized) youth with agency necessary to navigate and dismantle systems of injustice (O’Donoghue et al. 2007). Beyond empowerment, research indicates that adult-youth relationships–which are critical to promoting youth voice–are strengthened by organizational participation in community action (O’Donoghue et al. 2007). Participation in activism and critical reflection allows students to feel empowered in the face of otherwise immobilizing structural oppression (Jennings et al. 2008).

Parent Involvement

Another key factor in afterschool programming associated with positive outcomes for Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, and women youth is parent engagement. According to Behnke et al.’s 2011 research, implementing parent-involvement programming in afterschool programs could play an essential role in youth’s academic success, especially those who are at risk of dropping out. In encouraging parent participation in afterschool activities, youth organizations have the opportunity to integrate student support systems. In doing so, students’ care becomes more holistic and cohesive, as each system of support mutually informs the other. Behnke et al. also finds that parent involvement in programming encourages parents to be more involved in their child’s academic life, as well as their life more generally. Afterschool programming that provides a model for families to explore their students’ academic interests may also generate additional motivation for students to engage in classwork. Finally, including parent voices in afterschool organizations can be critical in shaping cultural curriculum, as families often offer a wealth of cultural knowledge that can inform the creation of culturally responsive programming (Behnke et al. 2011).

Discussion

As United States youth recover from the social isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic–as well as the academic loss that accompanies virtual learning–there is arguably no better time to radically shift the paradigm from which we understand youth support and extracurricular programming. The fabric of youth-serving organizations has frayed from the chronic stress of accommodating students in a deeply challenging political, social, and educational moment. Moreover, the rekindling of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 and the United States reckoning with structural racism has made the present a fertile ground for the reimagining and reconstruction of the status quo. Our communities’ systems–including afterschool programming for our youth–are being questioned yet again, as parents, educators, and community organizers assert that symptoms-based solutions are not enough. Unlike before, there is a critical mass of political interest in systems-change in all of our nation’s structures, institutions, and organizations. For this reason, afterschool programs are ripe for change.

Implementing culturally responsive afterschool programming is particularly critical in addressing the systematic persecution of Black and Brown youth. In a nation where Black youth are suspended at 3 times the rate of their white peers (Loveless 2017) and nearly one in four latino children are arrested before their 28th birthday (Study: Half of Black Males, 40 Percent of White Males Arrested by Age 23) striking criminalization and exclusion permeate the childhoods of children of color. Instead of incarceration and marginalization, culturally responsive afterschool programs offer a different set of options to Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, and women youth. When afterschool programs embed cultural responsiveness into their curriculum, youth of color gain the opportunity to encounter their identity from a framework of richness and value. This assets-based paradigm diverges greatly from the conventional workings of the school-to-prison pipelines that condemns Black and Brown children as deviant and deficient from an early age. Robust culturally responsive curriculum carves out space for care and belonging for students who have been dismissed by their educational system.

In addition to grounding student experience in safety and belonging, youth of color in culturally responsive afterschool programming have the tools and support needed to develop student voice and engage in change-making. The power of culturally responsive afterschool programming is derived from its insistence on both care and consciousness-building (as well as its claims that the two are intrinsically connected). While students gain the relational care of accepting peers and adult leaders, they are also urged to step outside of their comfort zone to shape cultural curriculum and agitate for change. The recognition of students’ own agency is particularly important in today’s political context, as minoritized youth are pushed to the periphery and cycled into the school-to-prison pipeline. Consciousness-raising and the proliferation of student voice in afterschool activities provides students agency in the face of otherwise immobilizing injustice. Cultural responsiveness in afterschool programs is therefore a critically subversive practice, as it insists on making space for the voices of often disenfranchised students and acts upon the radical hope that students organizing for justice can undo the very systems that seek to deny them their agency.

Areas for future research

While there is a robust body of existing research on cultural responsiveness afterschool programming, significant gaps still exist. While there is significant convergence in the research on the importance of adult-youth relationships in cultivating student voice, agency, and social consciousness, we found little information on the role that caring peer relationships can play in advancing student outcomes. Especially for non-mentorship afterschool programs like the Boys and Girls Club of America, understanding the impact of caring peer relationships–as well as the steps to take to develop them–is an area for further research. Additionally, there is very little existing research on best practices for providing culturally-responsive programming to specifically diverse majority Black, Brown, LGBTQ+, and women communities. Many of the case studies of culturally responsive afterschool curriculum that we identified are focused on communities where there is a clear ethnic, gender majority (Rhodes & Schechter 2014, Ventura 2017). However, the research remains limited on how afterschool programs can best navigate deeply multicultural student bodies, where an affinity-group model may not be appropriate or may be adapted to tailor practices to students’ diverse cultural experiences. More research into these areas of investigation are crucial to the development of strong culturally responsive afterschool activities in all United States communities.

Conclusion

With the nationwide reckoning with racial injustice and an influx of state funding for Connecticut youth programs, afterschool organizations have the unique opportunity to radically reimagine programming to affirm the cultural identities of the youth they serve. For children of color who are criminalized and marginalized both in their schools and on the streets, afterschool organizations must adapt their programming to cultivate a community of safety and support. A review of the literature reveals that effective culturally-responsive afterschool programs are grounded in the following tenets: caring relationships, belonging, student voice, activism and parent involvement. If taken seriously, we believe that an organizational commitment to these tenets will provide marginalized youth the holistic support they need to flourish inside and outside of the classroom.